Two races to the moon are hotting up

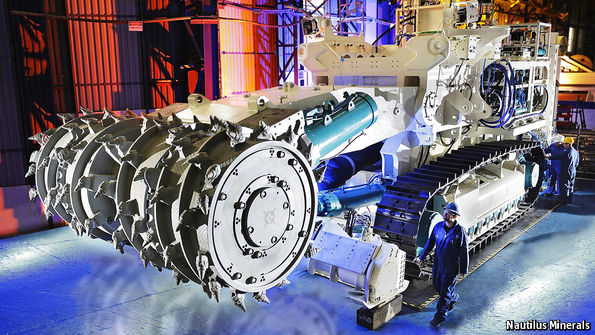

THE $30m Google Lunar XPRIZE has had a slow time of it. Set up in 2007, it originally required competitors to land robots on the moon by 2012. But the interest in returning to the moon that the prize sought to catalyse did not quickly materialise; faced with a dearth of likely winners, the XPRIZE Foundation was forced to push back its deadline again and again. Now, though, five competing teams have launch contracts to get their little marvels to the moon by the end of this year. And as those robotic explorers head into the final straight, a new contest is opening up.

On February 27th Elon Musk said that SpaceX, his aerospace company, had agreed to send two paying customers around the moon some time in 2018, using a new (and as yet untried) version of its Falcon rocket, the Falcon Heavy. They would be the first people to travel beyond low-Earth orbit since 1972. Two weeks before Mr Musk’s announcement, NASA said it was considering using the first flight of its new rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS), to do something similar, though with astronauts, not paying tourists. The race, it seems, is on.

This is not, though, a simple story of…Continue reading

Source: Economist