3D printing and clever computers could revolutionise construction

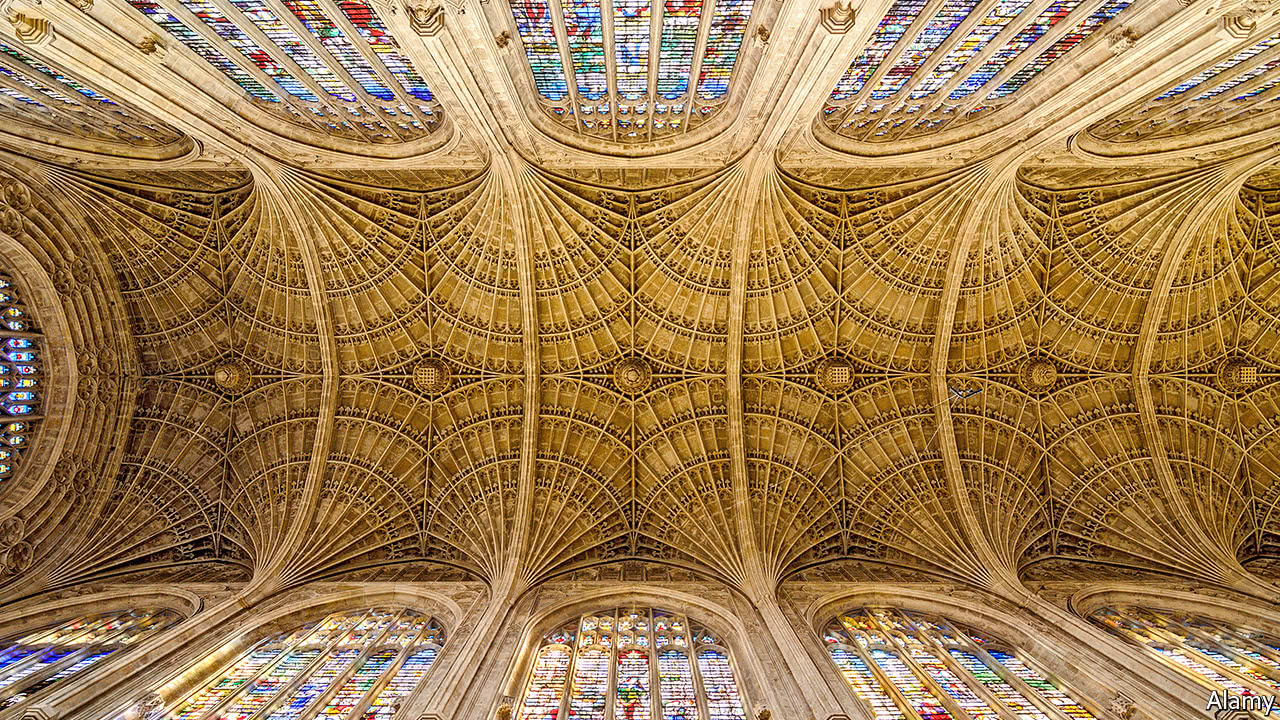

SET in the heart of Cambridge, the chapel at King’s College is rightly famous. Built in the Gothic style, and finished in 1515, its ceiling is particularly remarkable. From below it looks like a living web of stone (see picture below). Few know that the delicate masonry is strong enough that it is possible to walk on top of the ceiling’s shallow vault, in the gap beneath the timber roof.

These days such structures have fallen out of fashion. They are too complicated for the methods employed by most modern builders, and the skilled labour required to produce them is scarce and pricey. Now, though, new technologies are beginning to bring this kind of construction back within reach. Powerful computers allow designers to envisage structures that squeeze more out of the compromise between utility, aesthetics and cost. And 3D printing can help turn those complicated, intricate designs into reality.

In a factory that makes precast concrete, 16km south of Doncaster, in northern England,…Continue reading

Source: Economist