Magnetic moments

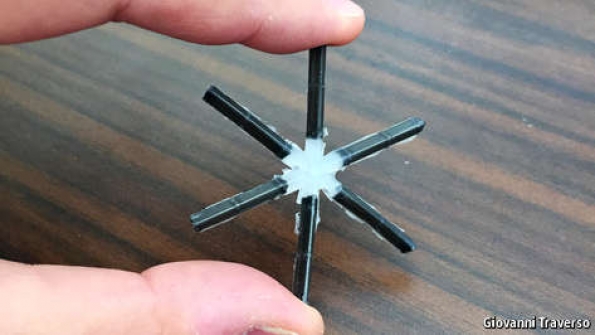

A CLASSIC experiment beloved of scientifically inclined children is to cover a magnet with a piece of paper and sprinkle iron filings onto the paper. This reveals the field lines that connect the magnet’s north and south poles. Try something similar with some of the new types of magnets now being made using additive manufacturing (3D printing), and a rather different image might appear. Unlike the simple bars and horseshoes of children’s magnets, the 3D-printed variety can be made in all manner of shapes. Their fields can thus be tailored into patterns far more complex than a simple north-south alignment.

These unconventional magnets have huge value in the design and performance of many products that rely on magnetic components: from hospital body-scanners to audio speakers, and from hard disks to wind turbines. In particular, anything that involves an electric motor or a generator also uses magnets. A modern car, for instance, contains a hundred or more electric motors of various sorts, to open and close the windows, adjust the seats, run the heating and, increasingly, to turn the wheels. All require magnets to make them work. The unconventional…Continue reading

Source: Economist